History of the Plymouth Silver King

Reprinted By Permission from Antique Power (July Aug. 1991)

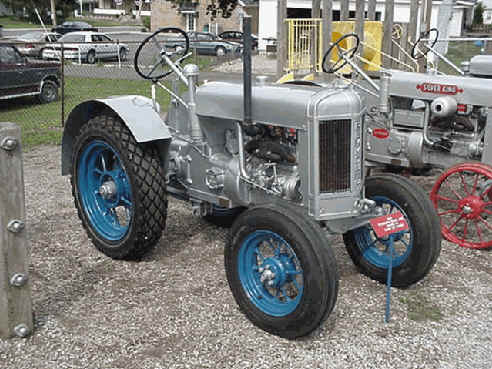

A Model 42 Silver King A Model 10-20 Plymouth

The little town of Plymouth

appears as no more than a dot on the map of Ohio, but has played a big part in

America's agricultural history. In the late 1800's, Pennsylvania brickyard

worker J.D. Fate and his business partner were attracted to this little town in

north central Ohio by the community's promise to help them found an industry

that would bring jobs to the area. The Fate and Gunsaullus Co. began building

clay extruding machinery for making bricks in 1882. In 1892 Fate bought out his

partner and formed the J.D. Fate Company, still making clay machinery.

In 1909 Fate organized the Plymouth truck company,

building motor trucks under the trade name "Plymouth". The

organization wasn't a great success and the Plymouth Truck Company went out of

business in 1915, after building fewer than 200 trucks and a single car.

Part of the failure of the Plymouth truck and car

business may have been the success of another of J.D. Fates enterprises. About

the same time the trucks were being built, a clay machinery customer asked Fate

if he could build a machine that would replace the mules then being used to move

rail cars around the railroad yard at his plant. Fate's yard locomotive proved

to be very successful, and laid the foundation for what would become the

company's primary product, Plymouth Locomotives.

In 1919 Fate joined with Root-Heath Manufacturing Company and

formed Fate-Root-Heath. The new organization continued to build clay machinery,

yard locomotives, and added a line of sharpening equipment for reel type grass

mowers. Business was good, and the company prospered until the economic crash of

1929.

By the early 1930's orders for expensive

locomotives had slowed to a trickle. In order to keep the factory doors open,

Fate-Root-Heath needed a product that was cheap enough that people could afford

to buy in quantity. The town of Plymouth was located in the middle of prime Ohio

farm land; a farm tractor would be a natural addition to the product line. A

tractor was well within the company's engineering and production capabilities.

Charles Heath, general manager of the company at that time, presented the idea

of building a farm tractor to get the company through the depression. An

employee recalls, "Charlie was the Kingpin of the operation. When Charlie

hollered, everyone jumped, from the president on down. " So Fate-Root-Heath

set out to build a farm tractor.

The first tractors were designed by the company's locomotive engineers, and looked it. Floyd Carter, chief engineer of the locomotive department, designed a huge, heavy affair powered by a big, slow speed Climax engine. This was just the kind of tractor farmers were turning away from in favor of lighter, more maneuverable machines. What was needed was a small, lightweight, inexpensive tractor.

This is a 1934 Plymouth tractor

Like the jobs in those days of the great depression,

engineering positions were in short supply. Engineers came from various parts of

the country seeking employment and bring with them new ideas on how farm

tractors should be designed. Several new engineers were hired, and design work

was begun on a new tractor.

An innovative new tractor was resulted-the

"Plymouth". The company had defined its niche in the farm tractor

market and designed a machine "...Built

for the 60 acre or less farm, but with a definite place as an auxiliary tractor

on the larger farm." The new machine was light, used a small, high speed

motor, and had a four speed transmission. The original Plymouth was Powered by a

Hercules IXA engine. It was a one plow standard tread tractor that could plow

all of 5 acres in a ten hour day. Its four speed transmission allowed a top

speed of an unheard of 25 mph. Fate-Root-Heath engineers had found a silver

paint that adhered well, gave protection against rust, and they were using on

their other products. The Plymouth tractors were painted this silver, with blue

wheels for contrast. The tractor weighed 2100 pounds and could be ordered in two

different tread widths, 38 and 44 inches.

Soon another engineer came to Fate-Root-Heath. Luke

Biggs, was a farmer who had built his own tractor, using an automobile engine

and a Ford T truck rear axle. One of the more original features of Mr. Biggs'

tractor was its single front wheel.

It was simple and it worked," says Mr. Biggs, "What more could a

fellow want?" Mr. Biggs showed Charlie Heath a picture of his home built

tractor, and was offered a job on the spot. Within a week of that first meeting,

Luke B. Biggs brought his farming and tractor building

experience to work with him at Fate-Root-Heath in the tractor department.

Within weeks, he was made superintendent of the tractor division.

The most revolutionary of the new "Plymouth"

tractor was that it was the first tractor ever to be designed from the ground up

to use rubber tires. "We put some on steel wheels" recalled Mr. Biggs,

"but when we delivered a tractor we always took along a set of rubber for

the farmer to try. I don't ever recall bringing a set of rubber tires back to

the plant after they were demonstrated. There were alot of steel wheels left

along the fence rows." Though the company sales literature promoted the use

of rubber tires, steel wheels were the standard equipment and rubber had to be

purchased at extra cost.

Right away Plymouth was to start a tradition that was

to forever confound and confuse dealers, collectors, and anyone else who showed

an interest in the tractors. The first Plymouths were given one of four

model numbers (R-38, R-44, S-38, S-44) determined solely by the tread

width and type of wheels used. A model R-38 was a tractor on rubber tires with

38 inch tread, an S-44 came on steel with a 44 inch tread, etc. As the model

line expanded, so did the quantity of model numbers until, at one time, there

were no less than ten model numbers to describe two basic tractors. In the

1940's the model number changed every year, even if the tractor didn't.

Chrysler corporation had been using the trade name for

their automobile since 1928. Apparently Chrysler had no complaint with the

Plymouth name on locomotives, but seeing little tractors buzzing down the road

at 25 mph with "Plymouth" on them was too much. In 1934

Fate-Root-Heath and Chrysler tangled over the use of the name. That single

Plymouth car built back in 1910, before Chrysler Corporation even existed saved

the day for Fate-Root-Heath. Chryslers high powered lawyers were sent packing

back to Detroit with their tails between their legs and Chrysler was forced to

buy the right to use the Plymouth name from Fate-Root-Heath, reportedly paying one dollar for it.

With the Plymouth name sold, the company had to come up

with a new name. Different proposals for a new name were thrown around. The

tractors had always been silver, and the Fate-Root-Heath men thought their

tractor was the "king". Charles Heath suggested the name "Silver

King", and it stuck. All tractors built in the plant after serial number

314 would carry the name Silver King.

By 1936 the tractor business was booming. Tractors were

going out the door at the rate of four or five a day. Mr. Biggs and his crew had

developed a three wheeled tractor that borrowed heavily from his homemade

design. This was the model R66 (or S66 for those few that were delivered with

steel wheels). The tractor employed a swinging drawbar that was attached to the

frame 18" ahead of the rear axle center line. In turns, the forward

attachment of the drawbar allowed the load being pulled to pull the front wheels

into the turn, eliminating the need for turning brakes. Designed as a row crop

cultivator tractor, the three wheeled model featured a unique steering

arrangement of levers and chains that formed a bulky appendage located out in

front of the radiator. This steering gear, though ugly, is effective, and was

cheap to manufacture. As Mr. Biggs said "What more could a fellow

want?" The first 1000 or so of the three wheeled tractors used a cast iron

frame; later ones used a steel plate frame along each side of the engine.

The low, stable design of the four wheel Silver King,

along with the lights and horn available, made it popular for a wide variety of

uses. The Works Progress Administration was paving highways and spending more on

keeping them mowed. The Silver Kings made perfect highway mowers. The little

tractors had plenty of power for the job, and with their rubber tires and high

road speed, they could get to and from the work area quickly. With optional bull

and pinion gear sets, the tractors would travel at up to 45 mph. They were also

popular in Hollywood, being used to tow movie sets around the lots of Warner

Brothers and other movie companies. California vegetable growers liked them

because in first gear they could tow a wagon through a field slowly enough for

the pickers to keep up with it, and then haul the loaded wagon over the roads to

collection points at high speeds, wasting little precious harvest time. Many

manufacturing concerns used Silver King industrial tractors. The Willys Jeep

plant in Toledo, Ohio, was a big user of Silver Kings.

Plymouth engineers were at work developing live

hydraulics, a three point hitch, and a completely hydraulic transmission in the

late 1930's. All the while the innovative little tractor was attracting

attention from all quarters. Henry Ford bought several, and stated that,

"The Silver King is the best tractor buy on the market." The engineers

entertained interested visits from the likes of Harry Ferguson, and a John Deere

sales manager was heard to say the Silver Kings was, "The best made poorest

sold tractor of its time."

Throughout the late 1930's tractors rolled off the

assembly line at a pace that did

more than just keep Fate-Root-Heath out of

bankruptcy. The assembly line had been fined tuned and when all the

necessary parts were available, a tractor could be turned out every 30 minutes.

The year 1937 was the best ever for Silver King production, with over 1000

tractors being built. Never again would the company build that many tractors in

one year. Engines and other items purchased outside the factory were bought

ahead in batches large enough to build 50 to 100 tractors. Often when parts were

reordered, the new item would be different from the one previously used. This

accounts for the variety in wheels, air filters, and especially paint colors

found on these tractors.

A Model 41 Silver King Orchard Silver King

The year 1938 brought the first change in the

appearance of the Silver King since the name Plymouth was removed in 1934. The

three wheeled tractor was fitted with a new, rounded, radiator grill. In 1939

the four wheel tractor also received the new grill. Many manufacturers were

streamlining their tractors at this time, and the new grill may have been an

attempt to streamline the Silver King. Few would agree that it was much of an

improvement on the looks of the three wheeled tractor, which still had the bulky

steering mechanism out front.

The first major mechanical change in production Silver

Kings came in 1940, with a switch to the continental built engine in the three

wheeled tractor (at serial number 4320). A Hercules IXB-3 engine was fitted to

the four wheel tractor for a time (#4341 to (#5319) before it, too, received the

Continental engine. Literature of

the day describes the engine as a Fate-Root-Heath design built for the company

by Continental. While Silver King marketing people may have wished this were

true, engineers consider this an overstatement of the relationship between the

two companies. Very few tractors were built during the war anyway, as material

for farm tractors was in short supply, and the war department had other plans

for Fate-Root-Heath.

World War II brought a huge demand for Plymouth yard

locomotives. The company worked at nearly capacity building locomotives and

other war material. Because of the demands of the War Department, tractor

production slowed to a trickle for the duration.

In 1942, the first big changes in the Silver King line

were introduced. An improved Continental F-162 engine was installed in all

models. Newly designed sheet metal was added to the tractor, and this time it

really did look streamlined. The steering on the three wheeler was simplified,

with a simple idler arm replacing the chain and sprocket previously used. The

lineup continued with a three wheeled model and a four wheeled model, with a

limited number of special tractors built that include combinations of old and

new parts.

After WW II the long denied need for tractors had

dozens of companies scrambling to meet the demand. At Fate-Root-Heath, the

demand for yard locomotives was just as strong, and the competition was much

less fierce. Tractor production continued, but the tractor division had much

less support from company management than it had enjoyed in the 1930's. Building

locomotives was, after all, the company's principal business. They had entered

the tractor market as a way to keep the doors open through the depression. In

the flush post-war business environment there was no longer any need for the

tractor division.

That didn't stop other companies from approaching

Fate-Root-Heath for help in meeting demand for tractors. Cockshutt bought

several tractors to evaluate and was favorably impressed. That resulted in a

request for Fate-Root-Heath to produce chassis and final drives for a tractor to

be built by Cockshutt. Interest at the company was low, so no arrangement was

made. a few chassis and final

drives were sent to the Harry Lowther Co in Shelbyville, Indiana for use in the

short lived Co-Op B2 Jr., but nothing came of that, either.

Engineers in the tractor division were constantly at

work improving the Silver King, even as support from above was eroding. New

hydraulics and other improvements were added in the years after the war. Luke

Biggs and the other engineers who were with the company in the 1930's had moved

on, but most of the men working on the line were farmers, too, and there was no

shortage of ideas for improvements.

Finally in 1954, Fate-Root-Heath management ran out of

tolerance for the tractor division. Parts and tooling were sent to the Mountain

State Fabricating Company in Clarksburg, West Virginia in February of that year.

Mountain State had sprung up during the war, doing government work, and was now

struggling to keep its doors open just as Fate-Root-Heath had decades before.

Unfortunately, even a successful product like the Silver King couldn't keep

Mountain State in business. Mountain State restarted the serial number series at

50000 and built approximately 75 tractors before sending the remaining parts

back to Plymouth. There, the parts were sent to a local junk yard, and

Fate-Root-Heath washed its hands of the Tractor business forever. Approximately

8700 Silver King and Plymouth tractors had been built.

Today, Silver King

tractors are remembered fondly by the farmers who farmed with them, the men who

built them, and the people of Plymouth, Ohio whose economy was sustained by the

little silver tractors through the depths of the depression.

Records and Silver King history that

existed at the Plymouth factory have all been lost or destroyed. All information

in this article was gathered through interviews with Silver King owners and past

employees. Particularly helpful were the late Luke B. Biggs, Don Shaver, A.K.

Kissell, Leon Hord, John Hoffman, Greg Hoffman, Donald Barnthouse, Tom Root, and

Ernest Green.

Click (Here) to go back to the Homepage.

Click Here to Visit SilverKingTractors.com for first time!